“Our ocean is 99% of our living space on the globe, we have huge dependency on the ocean in every possible way, but bottom trawling does a lot of damage,” Dr Amanda Vincent, Professor in Marine Conservation at The University of British Columbia told BBC’s Inside Science.

Bottom trawling or dredging is currently allowed in 90% of the UK’s MPAs, according to environmental campaigners Oceana, and the Environment Audit Committee (EAC) has called for a ban on it within them.

But some fishing communities have pushed back on the assertion that certain fishing practices need to be banned in these areas.

“Bottom trawling is only a destructive process if it’s taking place in the wrong place, otherwise, it is an efficient way to produce food from our seas,” Elspeth Macdonald, CEO of Scottish Fisherman’s Association told the BBC.

Scientists point to evidence that restricting the practice in some areas allows fish stocks to recover and be better in the long term for the industry.

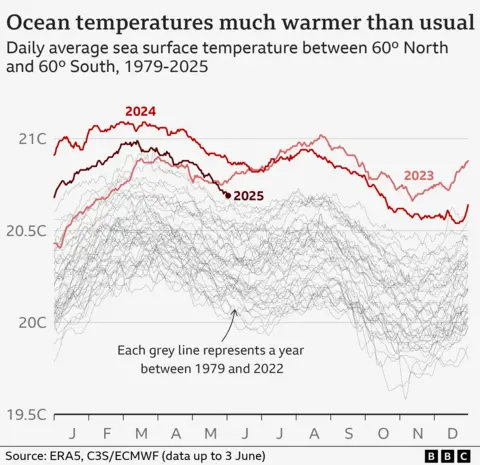

The conference had been called after concern by the UN that oceans were facing irreparable damage, particularly from climate change.

The oceans are a crucial buffer against the worst impacts of a warming planet, absorbing excess heat and greenhouse gases, said Callum Roberts, Professor of Marine Conservation at the University of Exeter.

“If the sea had not absorbed more than 90% of the excess heat that has been added to the planet as a result of greenhouse gas emissions, then the world wouldn’t just be one and a half degrees warmer it would be about 36 degrees warmer.

“Those of us who were left would be struggling with Death Valley temperatures everywhere,” he said.

This excess heat is having significant impacts on marine life, warn scientists.

Stéphane Lesbats

Stéphane Lesbats“Coral reefs, for the past 20 years, have been subject to mass bleaching and mass mortality and that is due to extreme temperatures,” said Dr Jean-Pierre Gattuso, senior research scientist at Laboratoire d’Océanographie de Villefranche and co-chair of the One Ocean Science Congress (OOSC).

“This really is the first marine ecosystem and perhaps the first ecosystem which is potentially subject to disappearance.”

The OOSC is a gathering of 2,000 of the world’s scientists, prior to the UN conference, where the latest data on ocean health is assessed and recommendations put forward to governments.

Alongside efforts on climate change the scientists recommended an end to deep sea activities.

The most controversial issue to be discussed is perhaps deep sea mining.

For more than a decade countries have been trying to agree how deep sea mining in international waters could work – how resources could be shared and environmental damage could be minimised.

But in April President Trump bypassed those discussions and signed an executive order saying he would permit mining within international waters.

China and France called it a breach of international law, although no formal legal proceedings have yet been started.

Scientists have warned that too little is understood about the ecosystems in the deep sea and therefore no commercial activities should go forward without more research.

“Deep sea biology is the most threatened of global biology, and of what we know the least. We must act with precaution where we don’t have the science,” said Prof Peter Haugan, Co-chair of the International Science Council Expert Group on the Ocean.